This summer (2025) marked the fiftieth anniversary of the release of the movie JAWS. National Geographic released a documentary: Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story.

Anyone can tell you that the iconic movie is about a shark that terrorizes a beachside town.

That’s the central conflict. So, it was fascinating to hear director Steven Spielberg say:

It’s about home. Longing for home, getting home, returning home, already being home.

I’d recently rewatched the movie with my son and hadn’t picked up on themes of home at all. The documentary flashed several scenes from the movie where characters talked about home, including the song Quint and Hooper drunkenly sing on the boat near the climax of the movie. Killing the shark and getting home was the overarching plot goal in the end.

In this post, I want to discuss the different layers of aboutness in your book. Your book is about your premise, it’s about your plot, it’s about your characters and their arc. And it’s also about something deeply personal. Something that only you can add to the mix.

Spielberg was 27 years old when he was making JAWS. He’d insisted on being on location in Martha’s Vineyard, rather than a movie set, and on using a mechanical shark beset with problems. He had a vision. But a May shoot turned into October. Spielberg was way over budget and over schedule. He was cold, often seasick, and terrified that he was going to be fired and would never work again. He regularly called his mother. All he wanted to do was be able to finish and go home.

The struggles, dilemmas, fears, and desires that come up in the process of writing your book are not separate from your book. They are often the key to what your book is about on a thematic level.

In On Writing, Stephen King writes:

It seems to me that every book – at least every one worth reading – is about something. Your job during or just after the first draft is to decide what something or somethings yours is about.

He goes on to say:

I have many interests, but only a few that are deep enough to power novels. These deep interests (I won’t quite call them obsessions) include how difficult it is – perhaps impossible! – to close Pandora’s technobox once it’s open (The Stand, The Tommyknockers, Firestarter).

I read The Stand and Firestarter, and like JAWS, I never picked up on the themes that drove the creator – despite extensive training!

As a lit major, I was rewarded for discovering and arguing obscure thematic elements in literature. This obscure and original mindset can be detrimental for an author, however. Authors want their work to be original and complex, but it’s a mistake to believe that because good literature can be about many things, it’s okay to write many things into a book.

Complex layers come from a well-defined premise, a character arc with a clear transformation, and plot events that provide that transformation along a defined timeline. The marriage of these elements create a cohesive story, a pattern that allows a reader to grasp thematic elements.

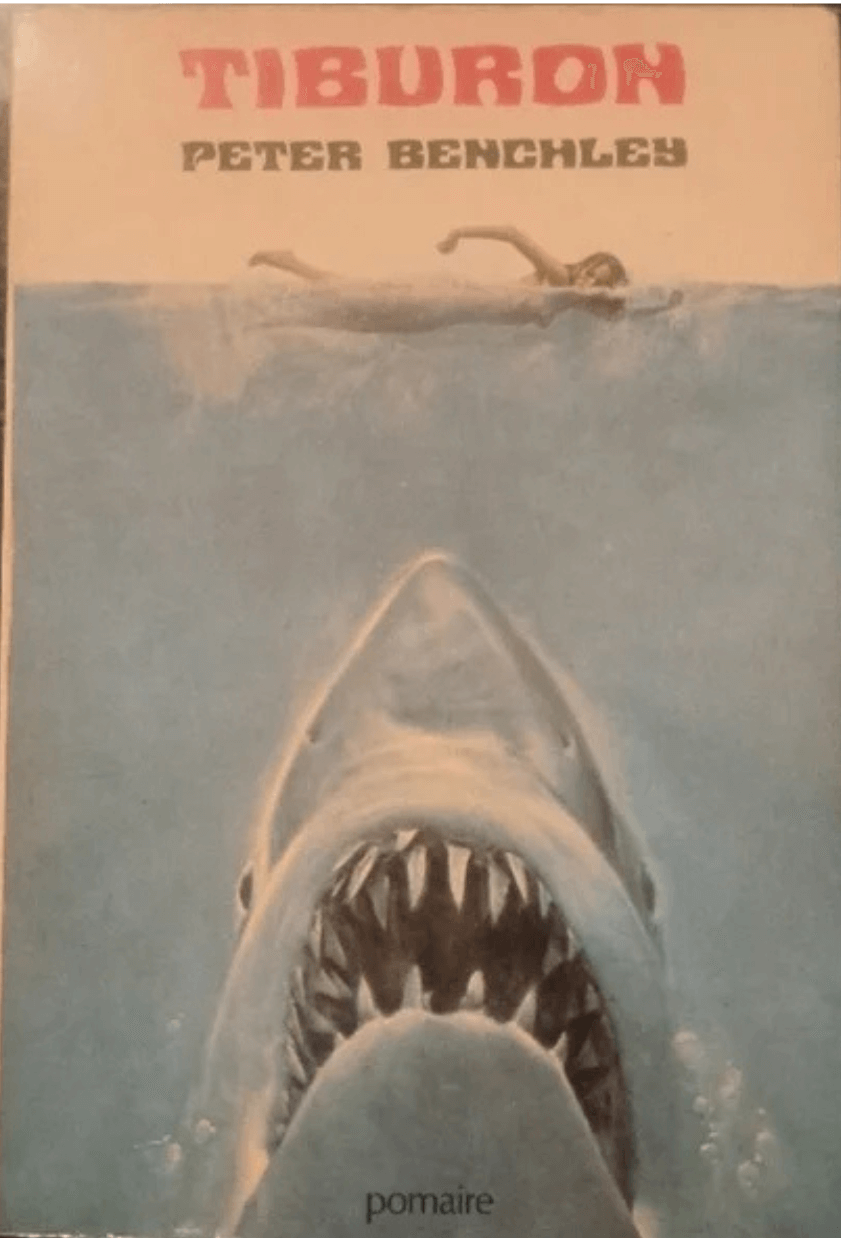

In the JAWS Documentary, Peter Benchley, author of the original novel, talks about how his favorite book review came from Fidel Castro.

When the Cuban communist leader was asked why he was reading a commercial American thriller, Castro answered that the book was a marvelous metaphor about the corruption of capitalism.

Is JAWS about the corruption of capitalism? Absolutely. That theme comes from plot – embodied by the character of the Mayor, who refuses to let the beaches be shut down on the busiest, and most profitable, weeks of the year.

This element of commerce over human safety and lives is important to the plot because if Brody had the power to shut the beaches down, the conflict, and the story, is over.

The plot supports not only the story conflict and character arc, but what the story is about. I’ve worked through plot events with authors that undermine, confuse, or conflict with what the story is about. I’ve found it’s not uncommon for memoir writers to shift what their story is about because of a certain event that they don’t want to leave out.

This is all part of the process – the plot (external) events of the story inform thematic elements of the story, and vise versa.

Figuring out what your story is about is difficult, but I hope this post encourages you to define your story’s aboutness on all levels. Because once you can focus and define narrative elements, you can craft them into a greater sum of their parts.

Readers will remember what they can visualize as they read. That’s action – exterior elements, your plot. But they will feel most vividly what the author feels, if the author is confident enough to craft it in to the story.

Here’s the good news: Unlike every other aspect of your book, you don’t have to make that part up. It’s already there! You’re already living it. Writers often try to quash the fears and anxieties crafting a book brings up. We tend to think that successful authors don’t feel, write, think, or act in a certain way.

Successful directors don’t call their mothers and long for home. But they do – the difference is that some intuitively infuse those relatable human foibles into their art. Others … make a movie that’s simply about a shark terrorizing a small beach town. But those aren’t the movies we’re still talking about fifty years later.

As a writer and an artist, it’s important to commune daily with the aboutness of your book. You don’t have to write every day, but let yourself feel. Get in touch with what you’re going through, what's obsessing you, or has obsessed you, and let that in to your daily practice.

0 Comments